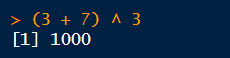

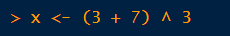

When you type an expression at the console and hit enter, R will evaluate the expression and print the result at the console.

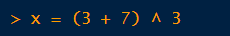

When you save or assign the result of an expression to an object, R will not print the value at the console.

R has two assignment operators:

=

<-

To view the value of an object, you can enter it at the console.

Once defined, an object can be used in subsequent expressions.

Objects are stored in memory. They will disappear when you shut down R (unless you tell RStudio to auto-save and reload objects in memory).

Every object has a data type or class.

Common data types:

numeric

character

factor

date

data frame, tibble

matrix

list

The rules for naming objects are pretty flexible. You can use numbers, letters, and most special characters.

A few rules to take note of:

There are a handful of popular naming styles. Pick one that you like, and be consistent!

| Style | Example |

|---|---|

| alllowercase | adjustcolor |

| period.separated | shoe.size |

| underscore_separated (aka snake case) | numeric_version |

| lowerCamelCase | addTaskCallback |

| UpperCamelCase | SignatureMethod |

Top five advantages of using scripts over the console:

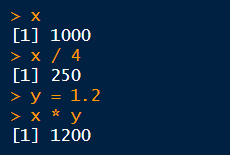

Similar to scripts, but can also include paragraph text, headings, pictures, formatting, etc.

R supports RMarkdown and Quarto markdown (similar).

R code is included in “code chunks” that get executed whenever you render the Notebook.

Notebooks are great when the desired output is an HTML document, PDF, Word Doc, etc.

For code that you want to repeat often, use a script.

The keys to R’s superpowers are functions! There are four things you need to know to use a function:

|

Finding the right R function, half the battle is. - Jedi MasteR Yoda |

|

Ask your friends

Ask Google / ChatGPT

Every function has a help page. To get to it enter ?

followed by the name of the function (without parentheses):

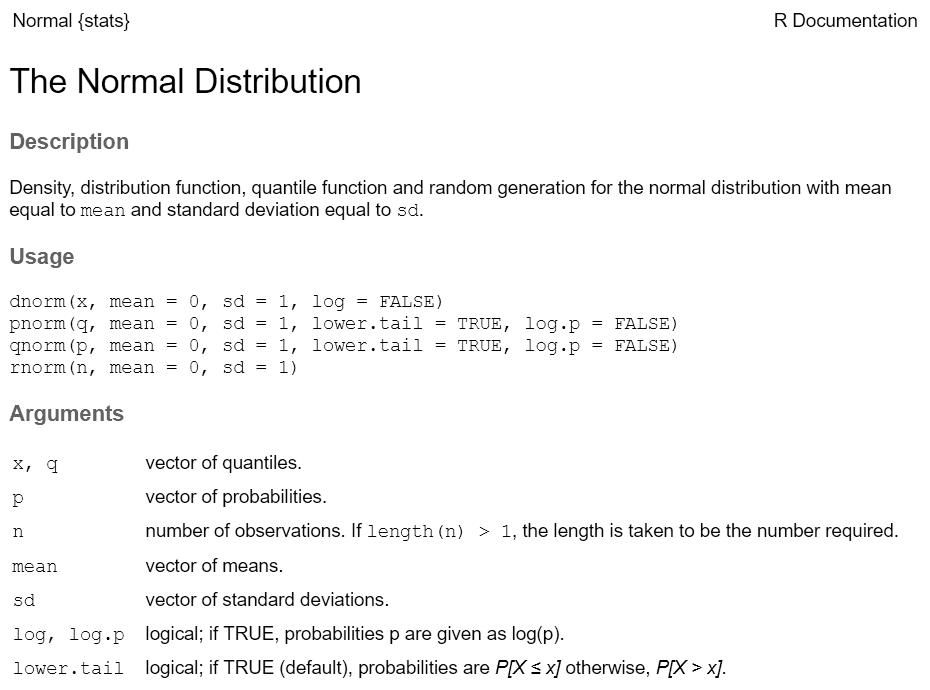

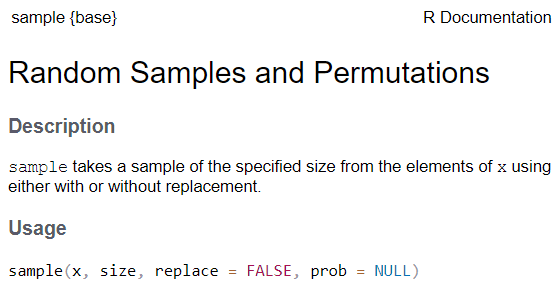

Most functions take arguments. Arguments can be required or optional (i.e. have a default value).

See the function’s help page to determine which arguments are expected. Example:

x and size have no default value → they are

required

replace and prob have default values → they

are optional

All arguments have names. You can explicitly name arguments when calling a function as follows:

Benefits of naming your arguments:

But you can omit argument names if you pass them in the order expected and don’t skip any.

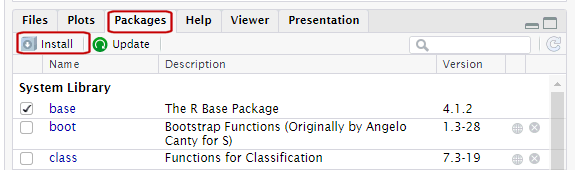

Packages are what R calls extensions or add-ons.

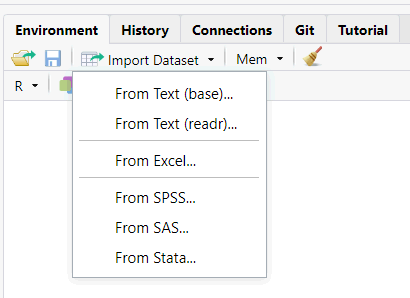

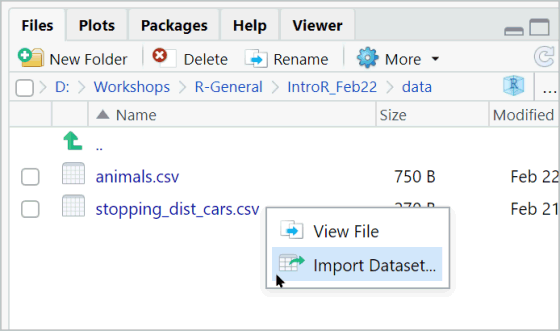

Three simple steps to use the functions in a package:

Figure out which package you need

Install (i.e., download) it (just once)

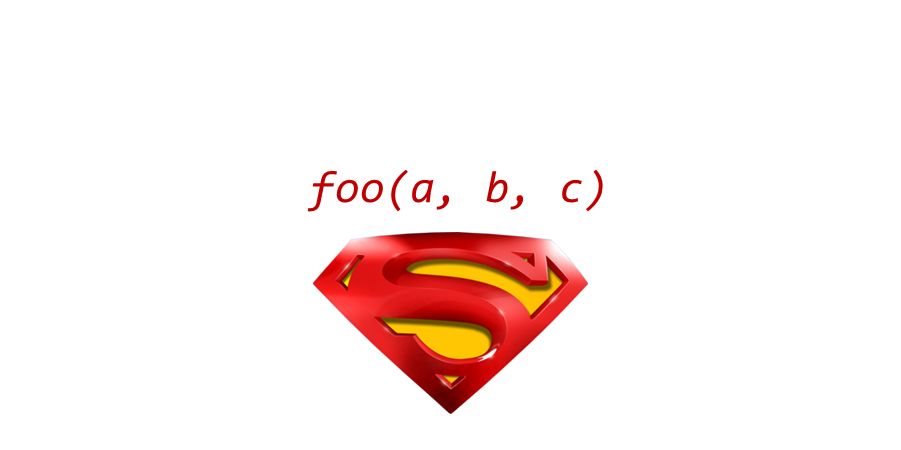

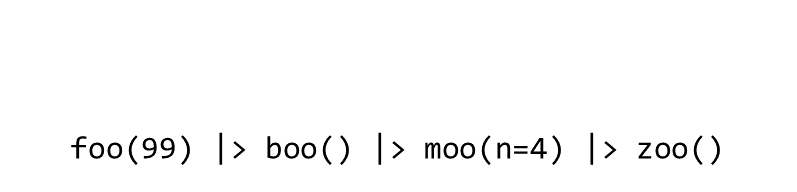

Piping syntax is an alternative syntax for chaining together functions.

With piping, you use the pipe operator |> (or %>%) to ‘feed’ the result of one function into the next function.

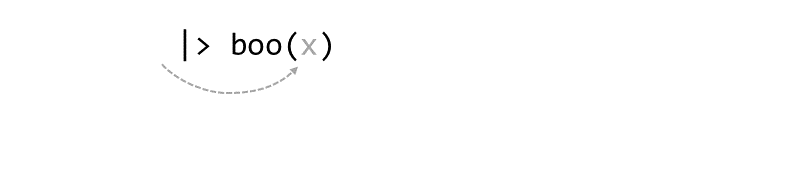

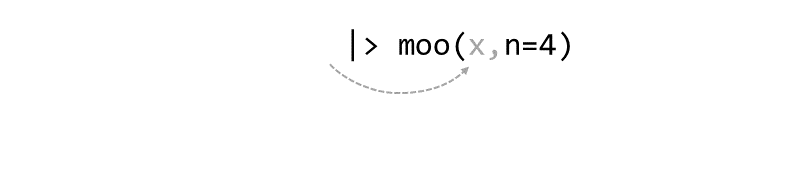

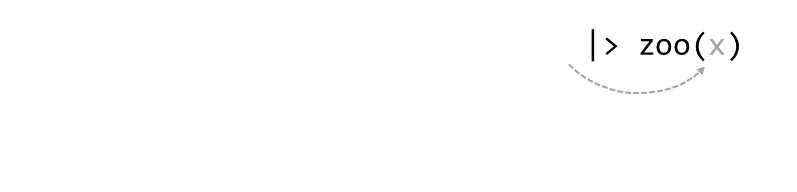

Piping allows the results of one function to be passed as the first argument of the next function. Hence a series of commands to be written like a sentence.

This generally requires functions that have been written to make changes to whatever object was passed in first argument, and return it.

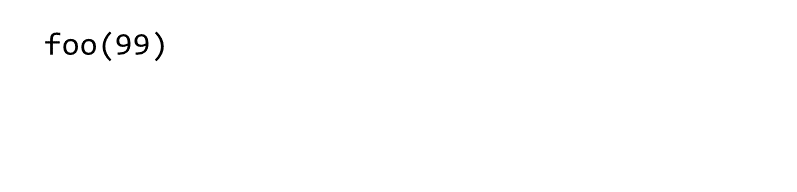

Consider the expression:

zoo(moo(boo(foo(99)),n=4))

Keyboard shortcut for inserting the pipe operator:

ctrl + shift + m

You can tell RStudio which pipe to insert under Global Options >> Code

|> (‘native’ pipe

introduced R4.0)

%>% (from

magrittr package)

To split a chain of functions across multiple lines, end each line with a pipe operator:

If the receiving function requires additional arguments, just add them starting with the 2nd argument (or use named arguments):

Occasionally two or more packages will have different functions that

use the same name.

When this happens, R will use whichever one was loaded first.

Best practice: use the package name and the :: reference

to specify which package a function is from.

When you use the package_name::function_name

syntax, you don’t actually have to first load the package with

library().

Resolving Name Conflicts with the conflicted

Package

When you call a function that exists in multiple packages, R uses whichever package was loaded first.

The conflicted package helps you avoid problems with

duplicate function names, by specifying which one to prioritize no

matter what order they were loaded.

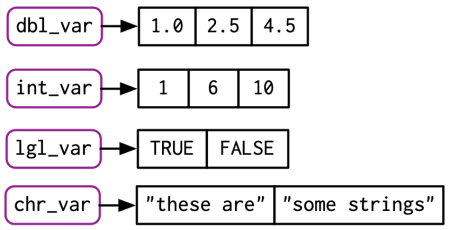

Vectors are R objects that contain multiple elements of the same class.

Example:

More examples:

In general, you need to use a function or operator to create a vector.

Example 1: Create a sequence of numbers with the

: operator:

Example 2: rep() function

Example 3: Random number functions

## [1] -1.6891683 -1.1048986 -0.6000753 2.2828762 0.1296368## [1] "January" "February" "March" "April" "May" "June"

## [7] "July" "August" "September" "October" "November" "December"## [1] "November" "December" "January"

Example 4: Manually combine elements with

c()

How big is my vector?

Many R functions and math operators are vectorized (i.e., operate on each individual element).

Example

First we create two numeric vectors:

Are sin() & cos() vectorized?

## [1] 0.0000000 0.8414710 0.9092974 0.1411200 -0.7568025## [1] 0.004425698 0.843853959 0.907446781 0.136737218 -0.759687913

Addition (and all math functions) is vectorized:

Functions that accept a vector and spit out a single value are called aggregate functions.

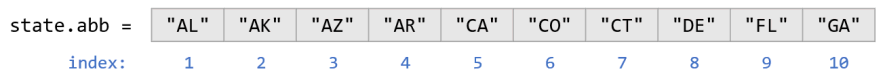

To extract a single element from a vector, you can use square bracket notation. Inside the square brackets, enter an expression that specifies which elements to return.

my_vector[ expression-which-identifies-specific-elements ]

To return multiple elements, pass a vector of indices.

You can also insert a vector of logical values (TRUE/FALSE) in the brackets. R will return the corresponding element for the TRUE values.

## [1] "March"

Better still, use an expression that returns a vector of logical values:

Example: Pull all out the months that start with ‘M’.

## [1] "J" "F" "M" "A" "M" "J" "J" "A" "S" "O" "N" "D"## [1] "March" "May"

R has two data classes that organize data in rows and columns:

rows

aka:

- record

- case

- observation

- feature (spatial)

columns

aka: variable, field

## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa

To get an individual column, use $

## Girth Height Volume

## 1 8.3 70 10.3

## 2 8.6 65 10.3

## 3 8.8 63 10.2

## 4 10.5 72 16.4

## 5 10.7 81 18.8

## 6 10.8 83 19.7## [1] 70 65 63 72 81 83 66 75 80 75 79 76 76 69 75 74 85 86 71 64 78 80 74 72 77

## [26] 81 82 80 80 80 87## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 63 72 76 76 80 87

You can use square bracket notation or tidyverse methods (dplyr).